While the automotive aftermarket is likely to keep using adhesives, repairers might still be fascinated to hear about some new techniques that could someday alter how factories join auto glass.

Heriot-Watt University in the United Kingdom announced earlier this month they had successfully welded glass to metal with an “ultrafast laser system.”

The laser fires “very short, picosecond pulses of infrared light in tracks along the materials” to join the dissimilar materials, according to the college.

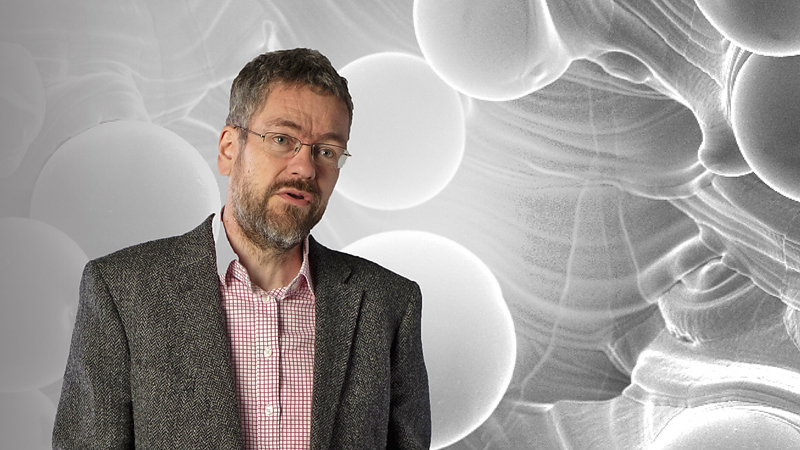

A picosecond is a trillionth of a second. EPSRC Centre for Innovative Manufacturing in Laser-based Production Processes director Duncan Hand called the difference between a picosecond and regular second “like a second compared to 30,000 years.”

The researchers were able to join quartz, sapphire and borosilicate glass to aluminum, stainless steel and titanium, according to the university.

“Traditionally it has been very difficult to weld together dissimilar materials like glass and metal due to their different thermal properties – the high temperatures and highly different thermal expansions involved cause the glass to shatter,” Hand said in a statement.

“Being able to weld glass and metals together will be a huge step forward in manufacturing and design flexibility.”

The university cited potential for aerospace and defense. It’d be interesting to see if there’d be an application for automotive windshields or glass roofs (which besides looking cool can improve aerodynamics). One wonders if someday a repairer would receive a pre-welded windshield or glass roof assembly from an OEM and join its metal components to the vehicle rather than gluing a piece of glass into place.

“At the moment, equipment and products that involve glass and metal are often held together by adhesives, which are messy to apply and parts can gradually creep, or move,” Hand said in a statement. “Outgassing is also an issue – organic chemicals from the adhesive can be gradually released and can lead to reduced product lifetime.”

Hand said the welds held up at -50 Celsius (-58 Fahrenheit) to 90 C (194 F), “so we know they are robust enough to cope with extreme conditions.”

The welding process works by generating a “microplasma,” according to Hand.

“The parts to be welded are placed in close contact, and the laser is focused through the optical material to provide a very small and highly intense spot at the interface between the two materials – we achieved megawatt peak power over an area just a few microns across,” Hand said in a statement.

“This creates a microplasma, like a tiny ball of lightning, inside the material, surrounded by a highly-confined melt region.”

NASA

NASA late last year described a similar finding using a laser firing at quadrillionths of a second (a “femtosecond”). They said the Goddard Space Flight Center had already joined glass to copper and to other glass; the team had also been able to “drill hair-sized pinholes in different materials.”

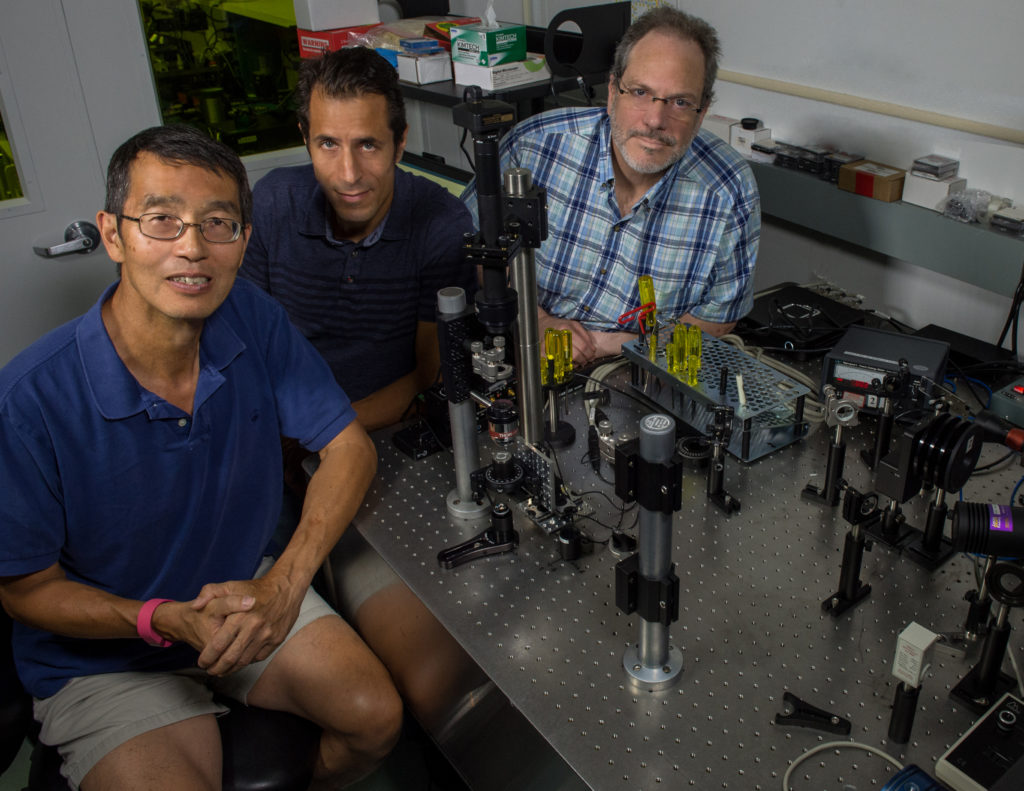

The team under optical physicist Robert Lafon was to also study joining titanium and aluminum. “The goal is to weld larger pieces of these materials and show that the laser technology is effective at adhering windows onto laser housings and optics to metal mounts, among other applications,” NASA wrote Nov. 1, 2018.

NASA explained, citing Lafon, that the laser doesn’t melt the two substrates being joined. “It vaporizes it without heating the surrounding matter,” NASA wrote.

This lets dissimilar materials be joined without glue, according to NASA.

“We want to get rid of epoxies,” Lafon said in a statement. “We have already begun reaching out to other groups and missions to see how these new capabilities might benefit their projects.”

More information:

“Welding breakthrough could transform manufacturing”

Heriot-Watt University, March 1, 2019

Images:

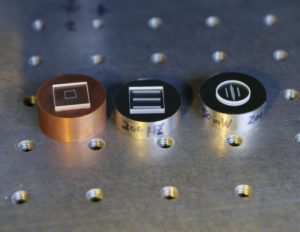

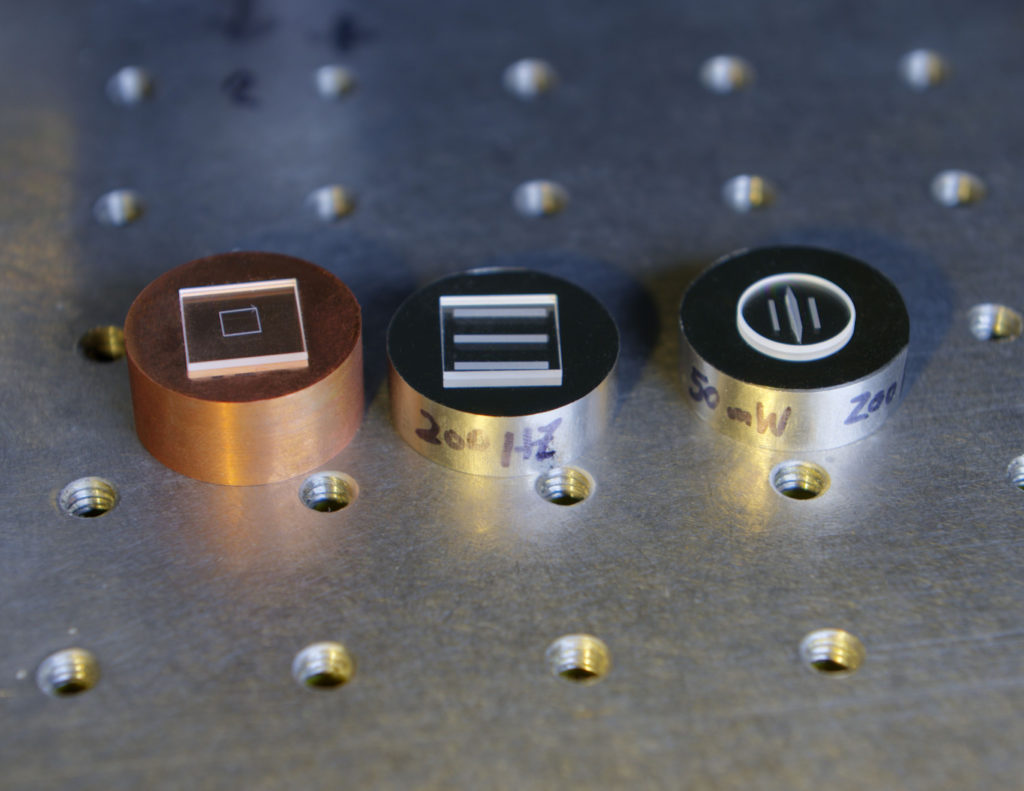

NASA on Nov. 1, 2018, reported that a laser firing at quadrillionths of a second was able to join, from left, silica (glass) to copper, silica to Invar and sapphire to Invar. (Bill Hrybyk/NASA)

EPSRC Centre for Innovative Manufacturing in Laser-based Production Processes director Duncan Hand, whose facility is based at Heriot-Watt University, is shown. (Provided by Heriot-Watt University)

From left, Steve Li, Frankie Micalizzi and Robert Lafon of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center are among scientists using what NASA called an “ultrafast laser” to join dissimilar materials. (Bill Hrybyk/NASA)

This article is care of www.repairerdrivennews.com

This article can be found here